Remembering Harold Washington

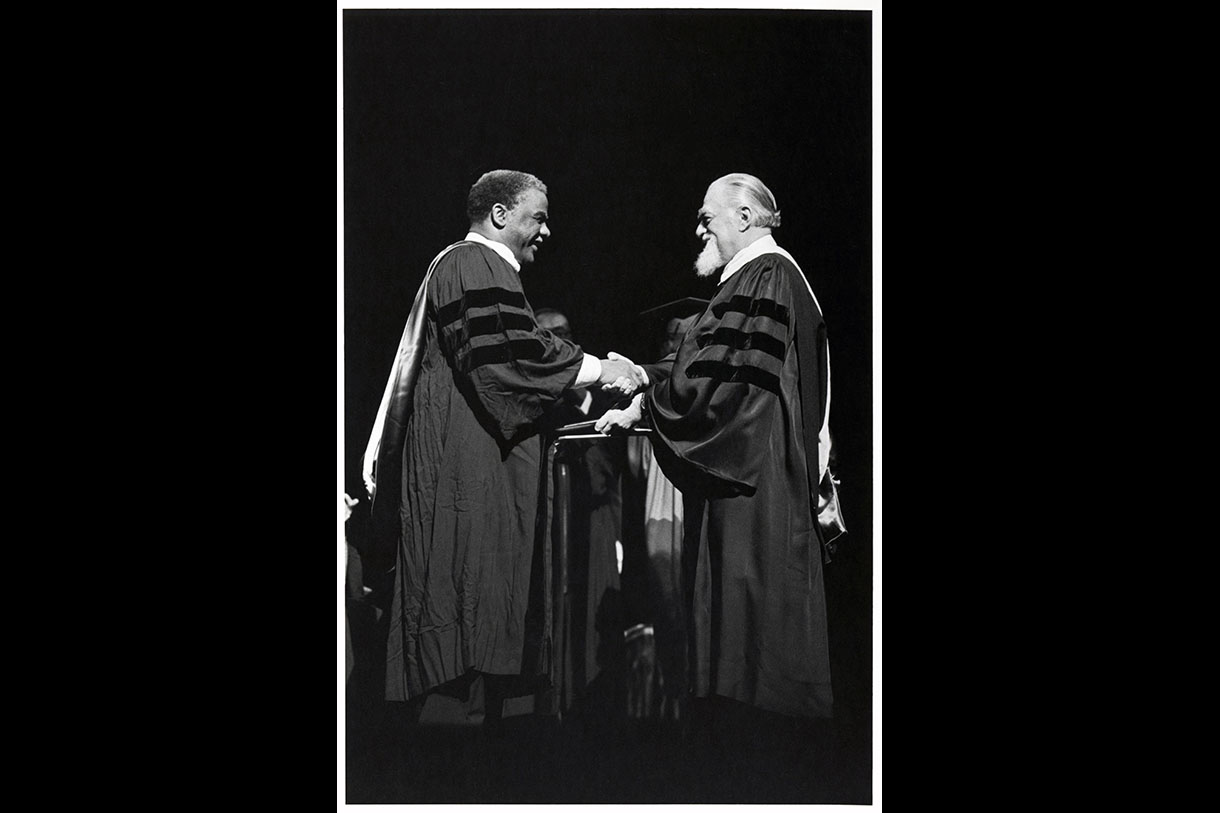

Harold Washington shakes hands with then-Columbia President Mirron (Mike) Alexandroff at the 1983 Commencement. Image courtesy: Columbia College Chicago Archives

Harold Washington shakes hands with then-Columbia President Mirron (Mike) Alexandroff at the 1983 Commencement. Image courtesy: Columbia College Chicago ArchivesThis past Saturday marked the 30th anniversary of the passing of Harold Washington, the first African-American mayor of Chicago and Columbia’s 1983 Honorary Degree Recipient. Washington, a lifelong Chicagoan who was born and raised in Bronzeville, attended Roosevelt College (now Roosevelt University) and Northwestern University School of Law before beginning his career in politics.

Washington first served in the Illinois House of Representatives for ten years before serving on the Illinois Senate from 1976-80. In 1980, Washington was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, representing Illinois’s 1st Congressional District, which comprises much of Chicago’s South Side and southwest suburbs.

Washington was sworn in as mayor on April 29, 1983. A little more than one month later, at Columbia College Chicago’s 1983 Commencement, Washington was awarded an Honorary Degree: Doctor of Humane Letters. He received the award from Pulitzer Prize winner and former Poetry faculty member Gwendolyn Brooks, who herself received Columbia’s first-ever Honorary Degree in 1964. The 1983 Commencement Program, preserved in the Columbia College Chicago Library Archives, describes Washington as “the tribune of a great city’s people and exemplar of the best aspirations of a democratic, equitable, and humane society.”

During his tenure as mayor, many prominent members of the Columbia community served in Washington’s administration, including:

Activist and long-time Humanities, History, and Social Sciences faculty member Rozell “Prexy” Nesbitt, who served as a special assistant to the mayor as part of an advisory group nick-named the “Mod Squad”

Former Columbia President John B. Duff, who in 1985 was appointed commissioner of the Chicago Public Library system and oversaw construction of the Harold Washington Library

And former Alderman David Orr, who in November 1987 balanced his time serving as vice-mayor with a partial course-load at Columbia teaching a political science course. When Harold Washington passed away unexpectedly, Orr, as vice-mayor, became interim mayor for one week until a successor was appointed, all while continuing to teach his “Urban Politics” course.

Two weeks ago on the PBS show Tavis Smiley, long-time Communication Associate Professor and Washington’s close friend and press secretary, Alton Miller, reflected on the unique challenges Washington faced: “Most big city mayors, when they want to begin a program of reconstruction, they have the assistance of the business community, they have the media in their corner — it’s a consensus that we need to be doing things differently from the way we used to. But when he came in there, one of the first things the downtown businesses tried to do was figure out how to make him a one-term mayor.”

Nesbitt, who by 1987 was working as a representative for the government of Mozambique, flew from Chimoio to Chicago on special request by President of Mozambique Joaquim Chissano upon hearing of Washington’s passing. As he stated in a Chicago Anti-Apartheid Movement Oral History housed at the College Archives & Special Collections, Nesbitt remembers Washington’s funeral as “a sad event” and also “a victory … I think that Harold’s contribution led to a victorious moment of citywide celebration and recognition of each other that we have never retreated from.”

A pioneer and a reformer who faced intense opposition from the Chicago City Council, many of whom were racially-motivated members of his own party, Washington was beloved by members of Chicago’s marginalized communities which had been overlooked and ignored by the notorious “Chicago machine” for decades. As mayor, Washington prioritized policies that would revitalize the city’s disenfranchised neighborhoods and frequently awarded subsidies and government contracts to local women and minority-owned businesses.

An ambassador for the city who worked to change Chicago’s cultural perception as “Al Capone’s town,” Washington easily won re-election in 1987, but suffered a heart attack in office the day before Thanksgiving and passed away on November 25, 1987. Washington’s contributions and impact on the city can be felt far and wide, and Columbia remembers and honors his legacy.