See It All with 360 Video

Six students looking at six GoPro cameras rigged to capture a 360 degree view. Photo courtesy of Mat Rappaport

Six students looking at six GoPro cameras rigged to capture a 360 degree view. Photo courtesy of Mat RappaportNote: To view the 360 videos on this page, use Chrome or Firefox.

In the four-minute video, we are on a small bed between two women, one playing a guitar, the other a ukulele. Between them, the words “my alternate universe” appear, the large white letters hovering near the wall. We are in the room and able to look in every possible direction. On the bed, there are phones, an open laptop, and a contraption holding up one of the few things that can’t be seen: a 360 video camera.

Having the freedom to view so many parts of the intimate space feels both disorienting and taboo. The piece was made by Interdisciplinary Book and Paper Arts graduate student Ruby Figueroa and created in a course taught by Mat Rappaport, associate professor of Television.

Figueroa’s “a story, the truth, and a screenplay” experiments with text and multiple layers composited onto the 360 spherical view.

Rappaport’s five-week, one-unit course is new. “With this technology, it seems like there’s something new every week,” says Rappaport. “We’re trying to work as agilely as possible to be able to respond to how fast it’s progressing.” Rappaport, who is also the president of the New Media Caucus, doesn’t have many curricular models to follow. “With this generation of immersive video, we’re doing it as early as anyone else is doing it.”

Currently being offered as a graduate topics course in Art and Art History, the idea of teaching 360 video first germinated in tvlab. Rappaport launched tvlab in 2014 with Television Associate Professor Kristin Pichaske as a hub for research, production, and innovation for students and faculty. They generate new media projects, some of which focus on virtual reality.

When Rappaport first prototyped teaching 360 video to students through directed studies in the fall of 2015, the Television department had one 360 video camera and a single workstation with the eclectic software required to edit and distribute the resulting video. At the beginning of this semester, they had three cameras. Now, there are five (including the two in the Art and Art History Department). Next fall, Rappaport will propose a three-credit course in 360 video, a first for Columbia.

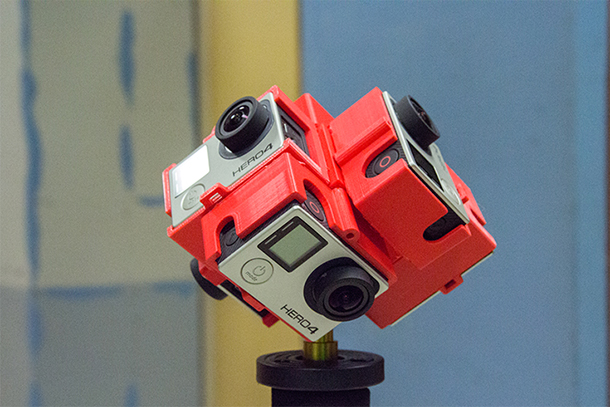

Rappaport used a Makerbot 3D printer to create a holder for six GoPro cameras.The holder was used for both the 360 graduate course and the Television Department’s Experimental Production and Editing course. Photo courtesy of Mat Rappaport.

Rappaport used a Makerbot 3D printer to create a holder for six GoPro cameras.The holder was used for both the 360 graduate course and the Television Department’s Experimental Production and Editing course. Photo courtesy of Mat Rappaport.

Currently, the leading producer of 360 media content is The New York Times’ “The Daily 360,” the kind of multimedia journalism that expands the borders of content creation. “The Daily 360” has only been around for eight months and their producer Maureen Towey recently Skyped into Rappaport’s class to talk to the students.

The New York Times creates a new 360 video every day.

“As a medium, 360 video works well for documentary but also for experimental and short narrative. The students in the course are prototyping all genres of content and are doing it successfully,” says Rappaport. “Working in this new terrain means having students reframe old questions. It’s a great test bed for working on content that will soon become mainstream that, for now, still has a very experimental thrust.”

But new media breeds new creative and ethical issues. Rappaport is conscious of this when he asks: “Is 360 video, or virtual reality (VR) video, truly a new media or is this within a long line of a media rhetoric about the potential for immersion? I think it’s the latter.”

Milk believes that “Clouds Over Sidra” is an “empathy machine” while others, like VR maker and scholar Robert Yang, call it a colonial “appropriation machine” that mines the experiences of others.

VR filmmaker Chris Milk thinks that “virtual reality is an empathy machine that lets the viewer inhabit other people’s shoes”—in essence, a machine that makes viewers more human. The counter argument, by media scholar Wendy HK Chun, is that “if you ‘walk in someone else's shoes,’ then you've taken their shoes.”

“I can see what it looks like at a Syrian refugee camp but as a professor in Chicago I get to turn my goggles off. In that sense, I have no responsibility,” says Rappaport. “These discussions are important to have with students working in any media so that they understand what the potential stakes are and what their responsibilities are as makers.”

Back to Figueroa’s film. In her piece, she says two things that can be guideposts for 360 video as it grows past its nascent form. First, we hear her voiceover call the video “a kind of self-assigned purgatory,” a liminal space between real and virtual. Secondly, Figueroa’s piece is an elegiac quest for home but she wisely asks if perhaps she has, vis-à-vis the video, already “found something better.”

Rappaport sees the potential in the form. “It’s moving really fast and quickly changing. Now, with the presence of 360 video on smartphones we can make and experience this technology without the cost and technical barrier of desktop VR. 360 video isn’t going away anytime soon. It’s just going to get more interesting.”

Additional Information:

Besides proposing the stand-alone 360 video course, Rappaport will add a 360 motion graphics design and animation module to his Motion Graphics 3 course. Also, any workstation with the newest version of Premiere Pro can be used for post-production.