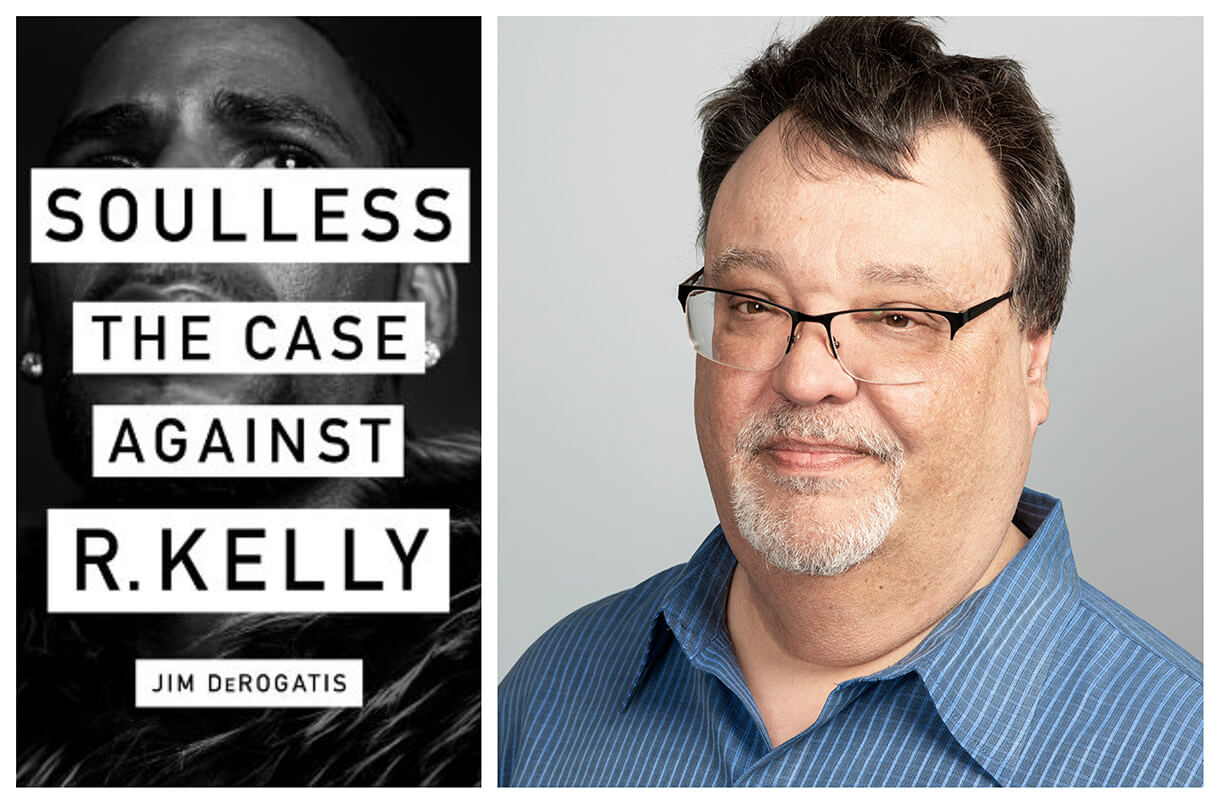

Jim DeRogatis and His New Book Make the Case Against R. Kelly

As a pop music critic and journalist, first at the Chicago Sun-Times and later as a freelancer, English and Creative Writing Associate Professor Jim DeRogatis has spent more than 18 years reporting on allegations that R&B superstar R. (Robert) Kelly sexually abused underage girls. DeRogatis has interviewed hundreds of people regarding the allegations and reported 50-plus stories, including a July 2017 BuzzFeed article that went viral and led to increasingly more scrutiny of Kelly by the media, the record industry, and law enforcement. After the January 2019 broadcast of the Lifetime docuseries Surviving R. Kelly, which built on DeRogatis’ investigation, Kelly’s record label RCA and parent company Sony dropped the singer from their roster. On February 22, 2019, Kelly was indicted on 10 counts of aggravated criminal sexual abuse—a class 2 felony—in Cook County, Illinois.

In part one of an interview, he talks about breaking the story in 2000 and advocating for truth for nearly two decades. DeRogatis’ forthcoming book Soulless: The Case Against R. Kelly will be released on June 4.

You broke this story in 2000 in the Chicago Sun-Times and you’ve been reporting on this case for more than 18 years. How much of the book was new reporting versus what you had already uncovered?

Everything that happened post-BuzzFeed 2017 was new, but it’s much more than that. There were three decades worth of connections that I hadn’t made, even as deep as I was into the story. I think there are a couple of really interesting new things in that I finally sat down with victim number one, Tiffany [Hawkins, the teen who filed the first lawsuit against Kelly]. There’s a lot of people I’d never been able to talk to until this book, like Carey Kelly, Robert’s half brother, and a lot of sources, on the [2008] prosecution team and elsewhere, were finally able to talk or felt freer to talk or felt disgusted enough to talk.

I think the biggest impact is that I lay it all out from 1991 until 2019. There are certain things in this multimedia age that only television does really well. … And then there are certain things that only audio does well. But only a book—this most Luddite of media forms—can take 130,000 words to tell this epic story. Only a book can show the cumulative predatory behavior of three decades—that’s when it hits you. We’ve got the churches and the schools and the courts and the cops and journalism and the music industry failing so many young women. It’s all in there.

You have been threatened over the years. In January 2001, a few weeks after you first broke the story, you received from an anonymous source a videotape that appeared to show Kelly having sex with a female who looked to be underage. The Sun-Times turned the tape over to the Chicago Police Department. That very same night, someone shot at your home while you were inside.

I still don’t know who shot out that window on Ashland Avenue.

And you don’t know who delivered those tapes either?

No. I have my theories. I tried to nail that down. I believe that there were many people out there who wanted R. Kelly to stop, but they were not going to go to a cop. They rightfully did not trust the legal system. [Chicago police officer] Jason Van Dyke was convicted of shooting Laquan McDonald 16 times and he essentially got a slap on the wrist, didn’t he? Compared to if that had been, you know, a black man shooting a white man, what would have happened? It makes sense to me why they trusted journalism more than the courts and the cops, and they thought we’d be able to help stop him.

I think about Tiffany Hawkins being brave enough to first go to the State’s Attorney in 1996 [to file a criminal complaint against Kelly]—1996!—and she’s sent packing: “We’re not interested.” It could have stopped then before the dozens and dozens of girls who followed. There’s no way you can get around the fact that this system, every level of it, failed.

Do you know why in 1996 the State’s Attorney’s Office refused her case?

Rather than me speculate, I will quote what Tiffany Hawkins says in the book. They were not going to believe a 15-year-old black girl. [By the time she filed the lawsuit] she was 19 or 20, but they weren’t going to believe a young black woman—not compared to a multimillionaire superstar who has in his pocket the Baptist power structure, who has the best lawyers money can buy, who has a crisis manager from Hollywood, who has an entire industry enabling him to prey on women.

You, Abdon Pallasch, and Mary Mitchell were the only ones reporting on this story for years. Why didn’t more news journalists cover this story?

I think there were many things. There was a fear of legal ramifications. I go into that stupid rivalry with the Tribune [in the book]. My response as a reporter if somebody scoops me is to come back with a scoop six times bigger: “I’ll show you!” That has never operated at the Tribune. … There’s the threat of controversial lawsuit. There are music publications not wanting to upset someplace where their bread is buttered: “We won’t get access to any of the Jive stars if we pick on R. Kelly.” There’s a lack in the cultural core of reportorial skills, or there’s young black girls: “We don’t care.” It always comes back to that for me. I think that the amount of attention given to a young white woman doing the most difficult thing she could possibly do, coming forward and saying she was assaulted, gets far more attention in comparison to the amount of attention given a young black woman, and I just don’t understand that.

You write about separating the art from the artist, and you suggest that fans have stuck by Kelly because perhaps they’ve decided his behavior doesn’t matter or they don’t care. But you don’t let your fellow music critics off the hook. About criticism you write: “The tools we have for this daunting task are insight, evidence, and context. What do you think the art is about, and how does it make you feel? Back up that analysis and emotional reaction with evidence, plenty of it. And, finally, know where the art came from and where it fits in our culture. Give context, because nothing exists in a vacuum. Nothing is just anything. Criticism of Kelly’s music after the first revelations about his predatory behavior had been, as my students would say, an epic fail. And it only got worse during the first nine years after his [2008] acquittal [on child pornography charges].” You specifically lay into Pitchfork, whom you criticized publicly for booking Kelly to headline its festival in 2013.

Pitchfork has been largely silent. Ryan Schreiber and Chris Kaskie, the two guys who pushed for Kelly’s booking, sold out not long after that [in 2015] to Conde Nast. Ann Powers and Jessica Hopper did a 180. I think a lot of younger critics are reassessing. I’ve yet to see the mea culpa from Maura Johnston [Village Voice, SPIN] or Kelefa Sanneh [The New York Times]. I think they should reconsider their earlier support for Kelly.

What do you think the deal is? Some critics like Jessica Hopper have suggested that perhaps some music critics just don’t know how to approach a story like this that’s complicated. Do you buy that?

I think that’s ridiculous. I do. You’re a critic. You’re moving through this world, analyzing this art, and what you see on the street doesn’t come into what you see in the art? I think we’re at a real period of trivialization of all art, not just music, where it’s just another consumer good.

When Jessica Hopper interviewed you in 2013 for the Village Voice, you offered to provide all of your Kelly files and research to any journalist who wanted access, to do their own investigation and reporting. Did anybody take you up on that?

No.

Not one person?

No. … I am this fat, white, middle-aged rock critic. I still don’t understand, what super power did I have? … People talked to me as a journalist because they were desperate to have somebody listen. And why more journalists haven’t listened I don’t understand.

Since the Surviving R. Kelly docuseries aired in January and after the February 22 indictments, there’s been a lot more media coverage of Kelly. How have you felt about the levelof reporting?

I can still count on less than the fingers on one hand the number of new pieces of this story that have broke, that haven’t been from a press release or a press conference. … Like someone who went out and dug up a story? Almost nobody.

What did you think of the R. Kelly interview with Gayle King on CBS This Morning in early March, when Kelly had a meltdown on national TV?

His Spotify numbers and iTunes downloads shot up after that. And if you look at what the kids and the sociologists call Black Twitter, it didn’t play bad. When Donald Trump says any of the things he says, it plays exactly into the hate-filled base of a certain portion of America. And that’s who he’s talking to. His brother Carey says in the book: He’s talking to motherf*ckers who are on his level. What does that mean? Other predators, other people who don’t see women as equal human beings—that’s really scary to me. It’s like white supremacists. I don’t know how anybody can listen to their ideas. Of course we don’t. We’re at one of the most vibrant art schools in America in the greatest city in America. We don’t see that, but let’s drive down to southern Illinois and we will.

You said in the book and you said it on February 22nd when the charges against R. Kelly came down for Cook County that federal authorities had wanted to take over the case a long, long time ago and Chicago wouldn’t allow it. What has been the response from authorities?

Still deafening silence, but a 26-member task force from the Department of Homeland Security, which has oversight into sex trafficking, has interviewed almost every name in my book—in Miami, in Chicago, in Los Angeles, in Atlanta, in New York. They have been spread out far and wide. Whether that ever leads to the Eastern District of New York convening a grand jury and issuing federal indictments, I don’t know. There’s also an FBI investigation, and U.S. attorneys have been interviewing people in New York and Chicago.

[Cook County State’s Attorney] Kim Foxx’s indictments are small compared to the scope of the crime. You’re still not seeing the scope of the crime, which is dozens and dozens and dozens of young women over 30 years, and people who helped him, whether it was literally passing along his phone number, putting it in the palm of the girl’s hand—I don’t know why that detail always freaks me out, but it does. The record company who turned a blind eye. I mean, it’s like everybody enabled this.

It feels like it’s too little too late. It really does. I was a decade late on the story in 2000. It had started in 1991 [with Tiffany Hawkins]. … But when that first story dropped December 21, 2000, it should have ended there. When he was indicted in 2002, it should have ended there. When he was tried in 2008, it should have ended there. How come it still ain’t ended? Harvey Weinstein’s done. Jeffrey Epstein is done. Kevin Spacey is done. Why the hell is R. Kelly not done? … He’s out of money now. If he gets out of this now, it’s some deeper, darker thing I can’t even figure out.

Speaking of the money issue: At the end of the book, you quote a February 26, 2019, headline from Margaret Sullivan of the Washington Post that read: “Decades of investigative reporting couldn’t touch R. Kelly. It took a Lifetime TV series and a hashtag.” You go on to say that none of those things would have been enough to stop him, that it came down to him running out of money.

Yeah. He has squandered about a quarter of a billion dollars in paying off young women, in paying off his enablers, in paying those attorneys and the crisis manager and 6-1/2 years of four attorneys and a crisis manager and who knows how many others on the team making between $500 and $850 an hour for 6-1/2 years.

That was to delay his trial until 2008?

Yeah. I mean, yikes. You or I would take one week of what one of those people were making and it would be our annual income.

In the book, you write that you met Kelly in person only once in 1995, and interviewed him only once, later that year. But since you started reporting on the abuse allegations, you hadn’t been allowed to talk to him. In a very memorable passage in the book, you write about being at South by Southwest in 2018 when Kelly’s manager Mason called to say that Kelly wanted to sit down with you to “clear the air.” You wanted the interview on the record and on video, and you asked your BuzzFeed editor for “the biggest, beefiest camera crew she could provide” and if you could expense a bulletproof vest. After you sent the questions in advance to Kelly’s camp, per their request, you never heard from them again?

No, no.

Would you want to interview him today?

I don’t think so because all he’s going to do is lie, and I don’t need to hear the lies. I’ve heard hundreds of people telling me the truth.

So you would not want to sit down with him, not even to look him in the eye and—

I suppose if they called today and said R. Kelly is willing to meet with you, I would do it. Of course I’d do it. And I have those questions from BuzzFeed. [I’d say] “I want to ask you about Tiffany Hawkins, Patrice Jones, Tracy Sampson, Montina Woods, Aaliyah D. Haughton. I’m going to name every one of those girls, and I want to hear out of your mouth that they’re all liars, one by one by one—because even as good as some of the reporters are now, there’s nobody else who knows all those names—and I’m going to throw them at you, every single one, and I want to hear you tell me how they’re all just out to get you. And around about the third or fourth, it’s going to become impossible to continue doing that.”

I speculate [in the book], and it’s just one sentence: I’ve always heard the spiritual anthems as a con and the bedroom jams as perhaps unwitting confessions. Convince me that’s otherwise. How do you continually pray to this God of yours … if these women are saying you ruined their lives, that five or six of them attempted suicide after being with you? How does that square with what you say you believe?

Are you still hearing from women and their families?

Yes. I talked to another woman who reached out to me this month. I don’t know if or when I’ll be writing about that. And I imagine that when the book comes out, I’ll continue to hear from others, just as I have for years. I would like to be done. But I’ll never not take the call.

When the book comes out in early June, it’s possible that many more women will come to you. Are you prepared to continue to follow the story?

Well, I would like to now have the luxury to sit back and be more analytical about it and [let reporters] Megan Crepeau and Morgan Greene and Tracy Swartz and Jason Meisner at the Chicago Tribune and Sam Charles at the Chicago Sun-Times and Bob Chiarito, The New York Times’ man on the ground in Chicago, [handle it]. They’re all very good reporters and I trust them.

But will they pursue the story?

They will, they will, they will. Whether their institutions will is a different story, but I think there’s other reporters ready to pick up that torch. At least, I hope so.