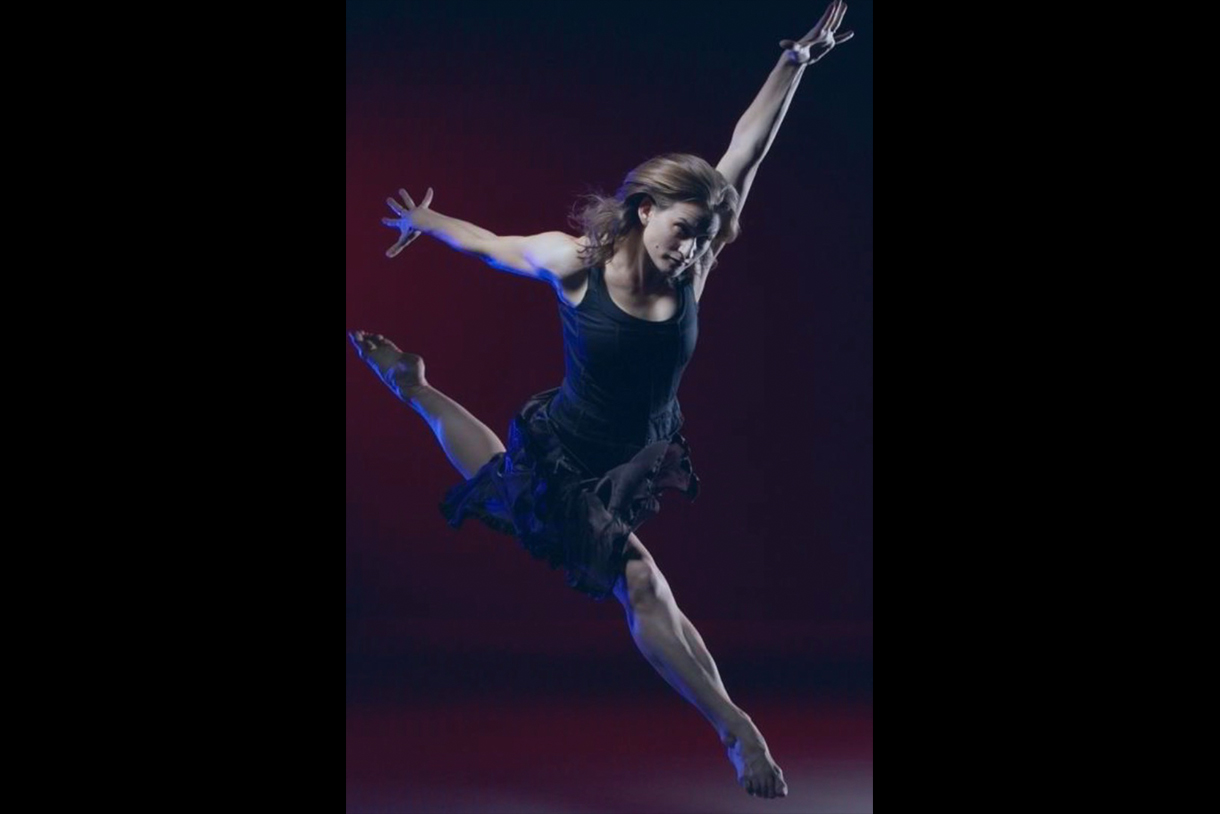

Columbia Dance Faculty Move in Sync with the Changing Educational Landscape

Like most educational institutions, Columbia College Chicago made the important decision last spring to halt in-person classes and pivot to remote instruction during the start of the COVID-19 global pandemic. The challenge to move dance online was unique given that instruction in the majority of its courses is hands-on. Still, dance instructors were able to maintain high quality instruction with a high touch to students while delivering coursework remotely. As the school moves to hybrid instruction, 36 percent of Dance courses will be taught online. They have incorporated the lessons learned this spring to upgrade experiences that were already top-notch.

“Dance is so much about human connection. The interaction with students in the studio is what drives us—working out complex movement phrases together, playing with musicality and rhythm, watching students devour the space or suddenly figure out how to make the movement material their own is an amazing thing to witness as a dance teacher,” says Paige Cunningham Caldarella, Associate Professor and Associate Chair at the Dance Center. “However, I understood that there was no other way considering the circumstances and as dancers always do, we problem solve and figure out a way to make it work.”

In addition to not being able to work in the same space at the same time, Dance faculty and students faced the challenge of working in their own spaces. “When we are all in the studio, it is an equal playing field. We all have the same space to move through with the same surface and the same options for moving safely at different levels—in and out of the floor, jumping, leaping, etcetera,” says Dardi McGinley Gallivan, Professor of Instruction at Columbia College Chicago. Moving to online learning changed this. “My students and I had various kinds of spatial restrictions—not enough space, carpeted surfaces, shared spaces, plenty of dogs, parents, and small children wandering through.”

Kelsa “K-Soul” Robinson, Assistant Professor of Instruction at Columbia, points out that Zoom and the technical difficulties relating to it were also a factor. She had to troubleshoot in order to figure out how to get the sound right so that students could hear the music loudly enough while also hearing her voice guiding them over it. Simultaneously, she had to have the music loud enough in her own space to hear it and demonstrate. “The delay from your computer to theirs makes it impossible to work with rhythm. I’m playing the music and their bodies are not syncing up to it at all so it’s impossible to tell if they are on beat. Then there are issues of depth and direction,” says Robinson. “It’s really hard for students to learn combinations that change direction and move through the space. I had to really talk them through in detail.”

These challenges moved Dance faculty to take on a new mindset and approach to teaching. “I remembered that this is what dance training prepares us for—the ability to adapt, problem solve, change direction and move on,” says Cunningham Caldarella. “I tried to think of it as another piece of complex choreography. How could I adapt the movement material to fit into smaller spaces? What music could I utilize to keep us in positive spirits and challenge us in new ways?”

Staying flexible to adapt to the limitations of being online and clear communication were key factors in meeting the challenges of remote learning. “The physical separation from my students truly inspired me to stay open in the communication department. You miss the subtle and not so subtle non-verbal cues when you are on a screen, so I worked to stay positive and available for the class,” says McGinley Gallivan. In addition, she stayed flexible while keeping her classes as close to ‘normal’ as possible by maintaining the class structure and expectations. “Certainly, many class elements had to change, but it seemed that the students responded well to maintaining ‘rituals’ and experiences we were originally connected to,” she says.

The use of video was also one of the most important components in meeting the challenges of dancing remotely. “Using video assignments was very helpful. Students would record themselves doing an exercise and analyze it based on my prompts. I will continue to use this in the future, I think that their generation is really connected to learning through video and that seeing/analyzing themselves through a screen is perhaps a more facile method for processing visual information than traditional ways like looking in the mirror in a studio,” says McGinley Gallivan.

Using video not only facilitated learning during remote instruction, but also exposed students to a broader range of choreographers and gave students an experience that more closely aligned with the origins of some of the dance forms they were studying.

Cunningham Caldarella provided video links and bios for two to three choreographers each week and asked students to upload a response of one minute or less that could be choreographed or improvised. She believes this helped students connect to a larger dance world that may not have been explored during a typical semester while also giving the students an opportunity to journal their dance during an unprecedented moment in education. “The studies that came out of this exploration sometimes brought me to tears. The resilience, commitment and kinetic exploration they demonstrated was astounding,” she says. “Selfishly, it also is what kept me going during our remote six weeks. I looked forward to seeing these ‘video diaries’ each week.”

In addition to also assigning weekly video challenges, Robinson layered a combination of diverse modes of learning switching from the particular to the conceptual. She stopped trying to get students to learn a specific move, step or combination in a very specific way, and instead focused on having students explore movement concepts that are embedded in the vocabulary and forms she teaches. “This is honestly much more true to the way I learned these forms in underground hip-hop and house music spaces, and the way the street dance community continues to train to this day. It’s always been a cultural space that rests on this organic symbiotic communication between individual expression and communal support,” she says. “In fact, the act of copying or doing something just like any other person is frowned upon. One of the most important values is finding your own unique ways of moving. But you have to be in tight relationship to the form and what has been ‘said’ before you (historically, communally, and in the moment); you demonstrate your connections to the whole, while putting your unique twist and flavor on it.”

Faculty also observed positive changes in students during remote instruction such as having classes grow stronger as a community over Zoom and some students becoming less introverted online.

Robinson, who came to Columbia as a community development consultant and then later became a faculty member in 2012 said she noticed a big change in student morale from the onset of the pandemic and moving courses online. “A lot of our students were vocal about how depressed they were feeling,” she says. “I think while they may have been frustrated at times learning dance technique through Zoom, the fact that they were physically moving did so much for their emotional state. They were releasing endorphins and moving collectively. And we all had a little window into the challenges we were each facing physically, and I think somehow it helped us all feel less alone to literally move through this struggle together. It really makes me emotional to think about how they were rising to the occasion… still getting up and dancing every week despite all of the literal obstacles in their way.”

“One of my favorite quotes by choreographer Alonzo King is so perfect for this moment in time,” says Cunningham Caldarella. “‘Dance training can't be separate from life training. Everything that comes into our lives is training. The qualities we admire in great dancing are the same qualities we admire in human beings—honesty, courage, fearlessness, generosity, wisdom, depth, compassion, and humanity.’”

MEDIA INQUIRIES

Daisy Franco

Communications Manager

dfranco@colum.edu

Recent News

- Students Excel When Following Passions in Columbia Core Curriculum

- Tomas Videla, MFA ’19, on Building a Life from His Love of Music

- Columbia Student Talks About Her Passion for Illustration

- Five Things to Check Out Online During Columbia's Winter Break

- Associate Professor Carmelo Esterrich to publish Star Wars Multiverse in 2021