Language Without Barriers

With Zoom meetings and video calls now filling our everyday lives, it’s become easy to take the technology for granted. Without it, though, some opportunities for learning and collaboration would never be possible.

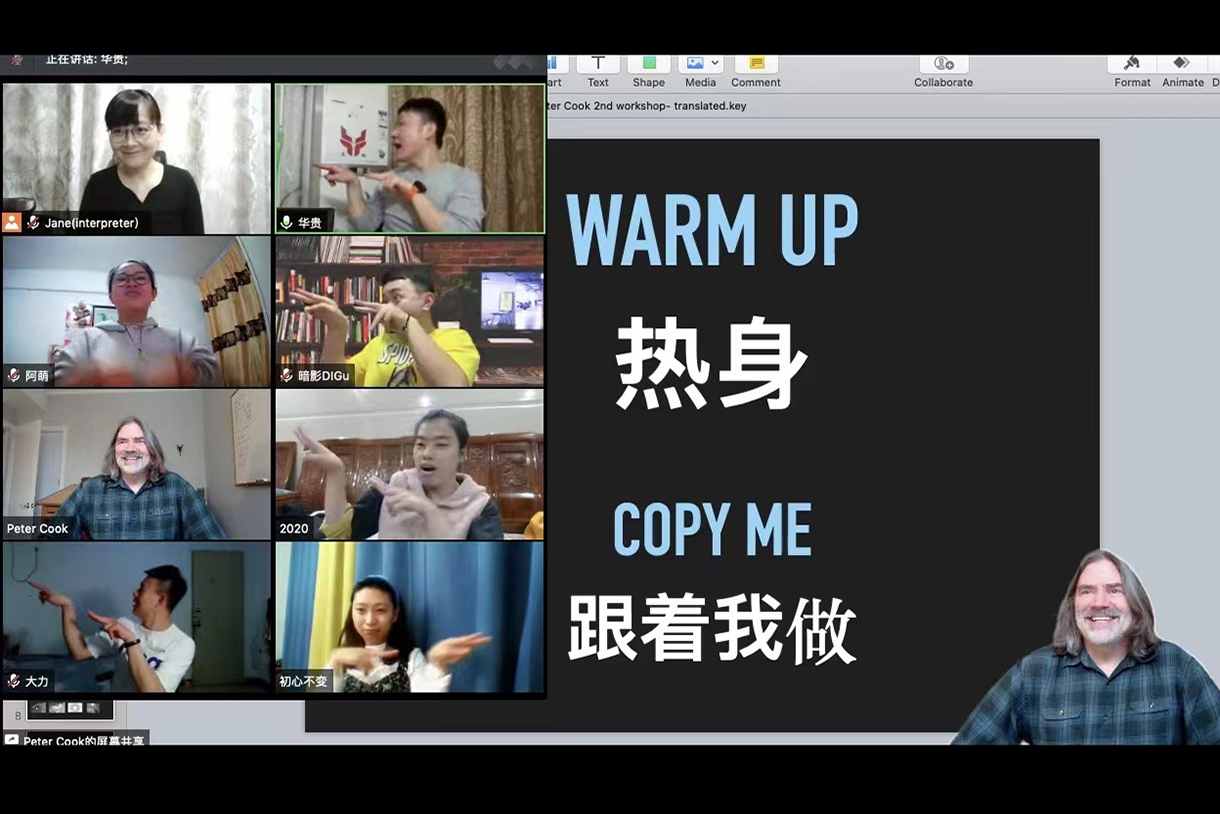

Associate Professor and American Sign Language Chair Peter Cook recently had the opportunity to participate in a virtual workshop with Deaf Chinese poets thousands of miles away; it’s the kind of event that has become more common since the beginning of the pandemic. The workshops, arranged by Rotterdam-based artist and performer, Raffia Li, were achieved through video technology and an American Sign Language-Chinese Sign Language interpreter.

The chance to work with these students and poets despite language and location barriers was an incredible learning experience for Cook and Li, as well as for the participants. “Technology has made everything amazing, even though I'm here in Chicago, I'm still able to interact with them,” he says. “It was a wonderful experience for everyone involved.”

On top of the standard technological challenges that come with communicating with someone on the other side of the world – such as securing internet connectivity, compatible applications, and the 13 hour-time difference – the biggest challenge was the language difference, as the Deaf Chinese poets use Chinese Sign Language (CSL). ASL and CSL interpreter Zhou Jiayi was available to translate and interpret the presentation, while Cook says he was able to use International Sign Language, which is often used in international meetings (including gestures, body language, facial expression, and classifiers), to give feedback to the participants.

Poetry has been a central part of Cook’s life for more than three decades. When he first began performing, and up until 2020, travel was an essential part of his work as a storyteller. For a while, Deaf and hard of hearing performers turned to video recordings and presentations, but those lacked the option of direct, immediate feedback and important conversations.

“Many Deaf people have been storytellers and poets without realizing it or putting a structure to further develop them,” says Li. "The workshop aimed to bring more exchanges between these performers, learning from Peter’s rich experience of working with sign language poetry.”

Li also says many participants were able to learn the difference between sign language poetry and Visual Vernacular, a more theatrical and expressive way of storytelling. “Different handshapes appear and transform in the digital space, but also shifting the body of each other’s,” Li says. “The screens were almost permeable by this joy and the unstoppable connection and kinship across the 12-hour time difference.”

This workshop also opened the possibly of welcoming the Deaf Chinese poets and performers to collaborate and showcase their work virtually to our students here at Columbia, says Cook.

As technology continues to advance, so do the opportunities for communication and collaboration in the Deaf community. Cook also regularly meets virtually with other Deaf artists from around the world – including some from South America, Europe, and Canada – to discuss their skills and current projects. This summer, he plans to work with an interactive media project by Assistant Professor Julie Chateauvert, in the Élisabeth Bruyère School of Social Innovation, Université Saint-Paul, Canada to develop a virtual reality to develop virtual ASL poems.

Other ASL faculty members at Columbia participate in virtual performances, lessons, and international workshops, as well. Crom Saunders is an Associate Professor in the ASL Department and has also performed for European Deaf organizations online.

Saunders says the boom in using online communication technology allowed him to continue presenting workshops and performing even throughout the pandemic. For example, he says, the World Shakespeare Congress (WSC) conference he was to attend in 2020 went virtual, which allowed him to still participate and hold a live Q&A session. “Barriers in the past would have been procuring qualified interpreters for events like the WSC on-site,” says Saunders. “Online presentations and collaborations have provided for lower cost bookings, and the opportunity to use qualified interpreters anywhere in the USA for communication facilitation.” The global pandemic also increased visibility of ASL interpreters and the world’s perception of sign language.

“This kind of opportunity serves a silver lining out of the pandemic restriction, because it allows us to bring guests aboard into our school, and vice versa,” Cook says. “We can learn about the diversity of sign language as well as Deaf communities around the world. That is a valuable experience.”

Recent News

- Columbia Holds Sixth Annual Hip-Hop Festival

- 5 Questions with Columbia Alum and Trustee Staci R. Collins Jackson

- Anchor and Reporter Paige Barnes ’21 Found Stories Worth Telling at Columbia

- Make Columbia Part of Your Holiday Season: Watch Alum Movies and Shows

- Fashion Design Alum Shaquita Reed ’18 Expresses Herself Using Different Mediums