Professor Dawoud Bey on His Approach to the Craft of Photography

World-renowned photographer, longtime Columbia College Chicago Photography professor, and father of notable Columbia alum Ramon Alvarez-Smikle '13, Dawoud Bey has been sharing the way he sees the world through the lens for more than 40 years. Since the mid 1970s, Bey has captured American history, place, and race in his imagery. In 1993 Bey worked with Columbia students through an eight-week residency at the Museum of Contemporary Photography. Five years later, he was contacted by Columbia about an open teaching position. He’s been bolstering Columbia students’ passion for photography ever since.

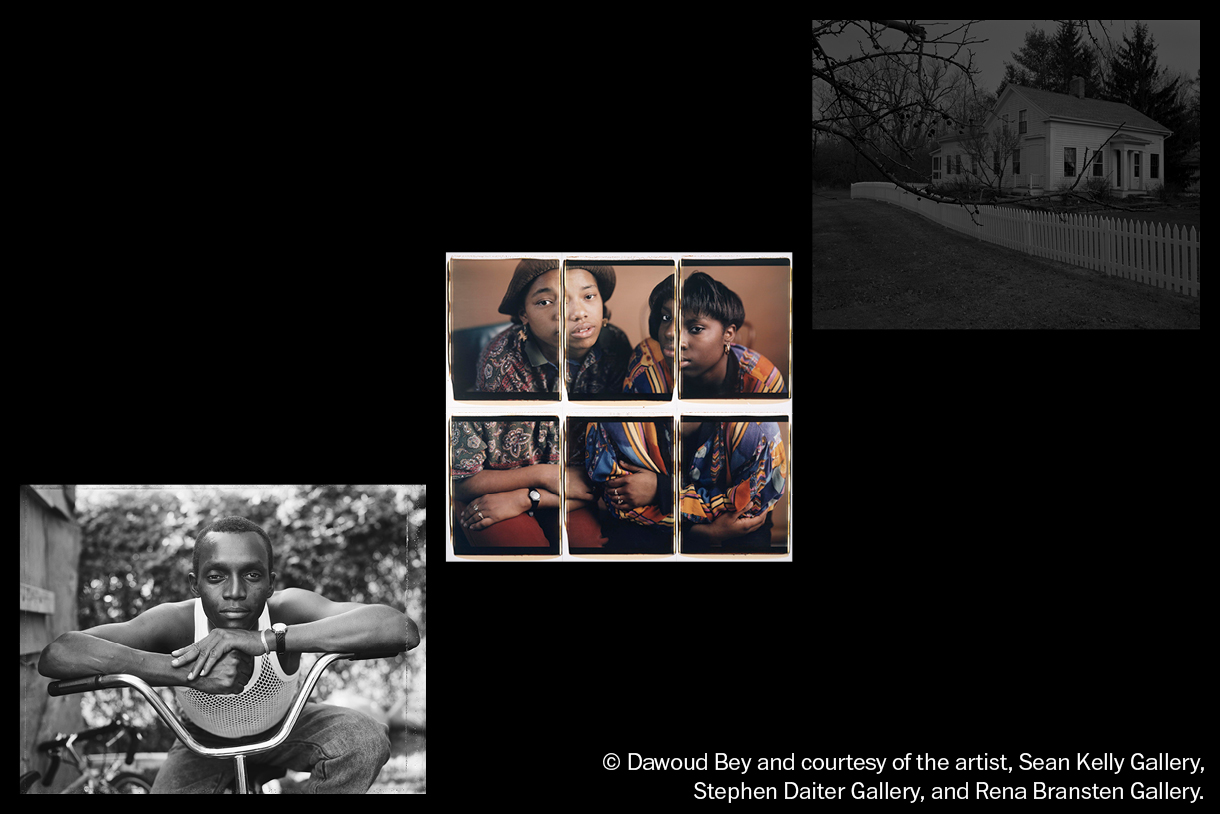

When Bey started creating photos in 1975, he was shooting with a small hand-held 35-millimeter camera and black and white film making pictures that were slow and deliberate. “The reason I was working that way was because a lot of the pictures that I had been looking at had been made with a large format camera,” he says. “It's just that at the early stage, I couldn't have told you what kind of camera they were made with. I just knew that as I continued looking at photographs, it was the photographs of ordinary people presenting themselves to the camera that really struck my interest more so than exactly how they had been made.”

As he continued working, the relationship between the photos he wanted to make became more formally and materially intentional. He began working with a large format camera. “I started to expand the way that I thought about the possibility of what the pictures could be, not only in terms of how they were made, but how they would function when they were displayed,” says Bey. “Imagining the places that I wanted to display the work and thinking about the difference between a small photograph and a large photograph in terms of giving the black presence an even more heightened physical presence within those spaces.”

His latest work, "In This Here Place”—named after a passage in Tony Morrison’s “Beloved”—is the third in a group of history related projects examining the African American experience. Bey uses the imagery in this latest project to provoke a reexamination of the past while also provoking conversations about how the past has affected the present. “History doesn't stay in the past and history, if you pay attention to it, pretty much explains everything,” says Bey.

“‘In This Here Place’ looks at the plantation landscape. It looks at the landscape that is the beginning of the formation of the set of relationships between African Americans and this country that continues to have very real meaning and relevance,” says Bey. “I'm looking at the landscape of enslavement and trying to provoke a conversation about that history in relation to the contemporary moment because I believe that there is a very straight line that can be drawn from that history of excessive abuse of black bodies and the contemporary narrative around how African Americans tend to fare in this country.”

The photos, which only feature landscapes, were taken in Hudson, Cleveland, and Northeastern, Ohio. “I made those photographs trying to imagine what that landscape might have looked like and felt like through the eyes of those who were moving through that space, trying to see as if through the eyes of a fugitive African American and moving through this landscape largely under the cover of darkness,” he says. “They're very dark photographs and they're very large. They kind of pull the viewer physically as well as visually into that space.”

Bey hopes that the images become an experience for audiences where the viewer can resonate with the photo through the basis of their own experiences. “None of those experiences I think are to be denied,” he says. “I have my intention, but when the work goes out into the world, it meets up with a whole range of responses. But mostly, I want the viewers to be provoked through the photograph into a deeper level of thinking about what the work is about than they may have otherwise been before coming to the work.”

It is important to Bey to depict a sense of what he calls a “rich black interiority,” which he defines as a rich and deep inner life and wide range of human emotions that black people experience intellectually and otherwise. “We do not merely exist in a state of racialized anguish. I think a lot of the narrative around the black subject is in some way justifiably about that, but that's not the sum total of who we are.”

“The kind of performance that I'm interested in in my portraits is one in which the person is basically performing themselves. It's a kind of heightened performance of oneself. It requires having a very light touch,” says Bey. “Because if it looks too much like a performance, we won't believe it. If it looks too self-conscious, it won't resonate.”

So how does Bey direct subjects to accomplish this kind of non-performance in which the person is performing themselves for the camera? “The only way I can explain it is to say that it's something that I know how to do very well. I know what it looks like when I'm seeing it. I know when to make the exposure. And it's all around taking that performance and giving it conspicuously public appearance to the exhibitions that I do,” he says. “But it's partially being a director and psychologist, someone who has a very real and deep interest in the human community because you can't make something visible if you don't believe in it.”

As an educator, Bey sees his role as being able to bring his 40 to 50 years of experience into the classroom and to make that available to his students. “I try to make students aware that I have been in some way thinking about and working with and practicing within this medium every day for probably twice as long as they've been alive, just to give it some context,” he says. “I can help them through my experience, figure something out that left to their own devices might take them a longer time to figure out.” Most importantly, he says, is to give students a sense of how being a photographer can matter and “how the act of being a photographer or an artist is not divorced or separated from being in conversation with the larger society.”

Dawoud Bey is a 2017 MacArthur Foundation Genius Fellowship awardee. He is also the recipient of fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, the United States Artists, and the National Endowment for the Arts, among other honors. His work has been featured in notable solo and group exhibitions worldwide and including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Brooklyn Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, the Museum of Contemporary Photography, the Museum of Modern Art, NY, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and other museums around the world.

MEDIA INQUIRIES

Daisy Franco

Communications Manager

dfranco@colum.edu

Recent News

- Columbia Holds Sixth Annual Hip-Hop Festival

- 5 Questions with Columbia Alum and Trustee Staci R. Collins Jackson

- Anchor and Reporter Paige Barnes ’21 Found Stories Worth Telling at Columbia

- Make Columbia Part of Your Holiday Season: Watch Alum Movies and Shows

- Fashion Design Alum Shaquita Reed ’18 Expresses Herself Using Different Mediums